How are traps, pots and other devices used, and can this method of fishing be sustainable?

What are traps?

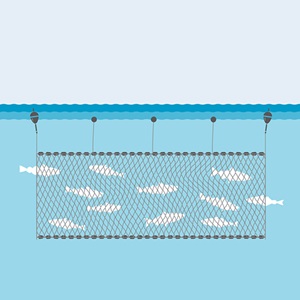

A ‘trap’ is the collective term for a diverse group of fishing gears which include pots, stationary nets, weirs and barrages. The design and method of use varies depending on the species being targeted and location of the fishery, but are all stationary devices that fish or shellfish enter voluntarily but cannot escape from.

Traps are typically set on the seabed and left submerged (“soaking”) before they are retrieved by the vessel and harvested. The soak time varies depending on the fishery and target species.

Using pots and traps

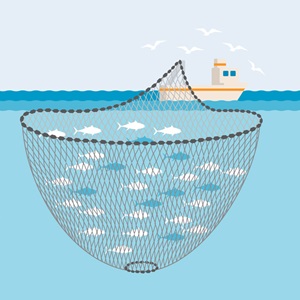

Many commercial fisheries use pots and other similar forms of traps to target species living on or near the seabed. This includes crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters, molluscs, and fish such as sea bass and eels.

These gears are characterised by a rigid, three-dimensional frame, wooden or mesh panels, and a tapered entrance to prevent the catch from escaping, and they can be used in a range of environments – from shallow, coastal waters, to offshore, deep-sea fisheries. Fishing vessels can deploy multiple traps attached to a single rope with a floating buoy at each end. Individual traps, which each have a single vertical rope connecting the trap to the surface, can also be used.

/pots-and-traps-illustration.tmb-large1920.jpg?Status=Master&Culture=en&sfvrsn=9c7b499f_1)

Can traps be used sustainably?

Traps are typically considered to be a selective and low impact method of fishing. However, these gears can have a detrimental effect on the marine environment if the fishery is not well-managed.

Biodegradable materials to prevent ghost fishing

Traps, along with other static fishing methods like gill nets, are more likely to get lost than other gear types as they are left unattended on the seabed. Loss occurs primarily due to bad weather, or interactions with marine traffic and other gear types.

Lost or discarded traps can seriously impact the environment, as they may continue to catch or entangle marine life ("ghost fishing"). Trapped fish and shellfish attract scavengers, which also become trapped creating a vicious cycle.

Fisheries should have effective management policies in place to reduce the risk of gear loss, and programs to monitor and retrieve any lost gear. This can include GPS tagging to locate lost gear, careful fisheries zoning to avoid conflict with marine traffic and other fishing activities, and gear disposal facilities at ports to incentivise fishers to discard gear responsibly.

Mitigation measures can also be taken to reduce the length of time lost gear can continue to trap marine species. This may include using biodegradable elements such as escape panels or locks.

Western Australia Rock Lobster fishermen with equipment © Matt Watson

Reducing risks of entanglement

Marine mammals and turtles are particularly vulnerable to entanglement in the ropes that connect pots and traps to each other and to buoys at the surface. Entanglements can prevent marine species from swimming or feeding properly and may cause potentially fatal injuries.

Different fisheries take different approaches to reduce their impact on vulnerable species, with the method used dependent on factors such as gear and vessel type, fishery location and environmental conditions.

These methods can include implementing seasonal or regional closures to avoid known habitats and migration routes, using rope with weak links, or connecting pots with rope that sinks to the seabed.

Some fisheries have also trialled technology that minimises the presence of ropes in the water column until the traps can be retrieved. This can include using a remote control system to trigger a retrieval mechanism, or 'galvanic timed releases' where rope is secured by a metal component and only released once the metal has corroded.

The MSC certified Western Australia rock lobster fishery reduced humpback

whale entanglements by approximately 60% following the introduction of government-mandated management measures. This included reducing the length of slack rope and number of floats at the surface. A Code of Practice was also introduced, which included

a clear process for reporting entanglements.

How MSC Certified fisheries are improving

As well as fishing healthy populations, fisheries must show they are managing their impacts on habitats and other marine species.

Modifying gear to reduce bycatch

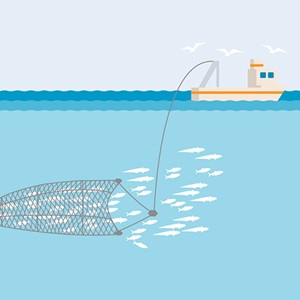

Pots and traps are typically designed to be selective for the target species: from the shape of the trap and entry mechanism to the type of bait used. However, the capture of unwanted or undersized species (bycatch) can still occur and fisheries should take steps to prevent it.

Bycatch can be reduced through methods such as adding escape rings, vents or hatches to the trap, or increasing the size of the holes in the mesh or side panels. This will enable individuals to escape if they are smaller than the minimum landing size of the target species.

All traps in the MSC certified Southern King crab fishery in the Argentine Sea are required to have at least three escape rings. Since the introduction of the rings, the proportion of undersized and female king crabs caught fell from 50% to 15%. Catch of non-target spider crabs also decreased by 92%.

Exclusion devices can also be used to prevent marine animals from entering pots, where they risk becoming stuck and drowning. The Western Australia rock lobster fishery totally eliminated sea lion bycatch, through the mandatory use of a blunt metal spike at the neck of the entrance to the pot.