With the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP 16) in Cali, Colombia underway, we must confront a critical imbalance: marine biodiversity is being largely neglected in global conservation efforts. This threatens our oceans and the planet’s health: terrestrial and marine ecosystems are interconnected - without a thriving ocean, life on land cannot flourish.

Around 80% of governments have failed to submit updated National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) ahead of the COP. These plans will set the stage for decades of work to protect nature. It is vital that they integrate marine biodiversity, securing necessary commitments and funding to protect our oceans alongside terrestrial ecosystems.

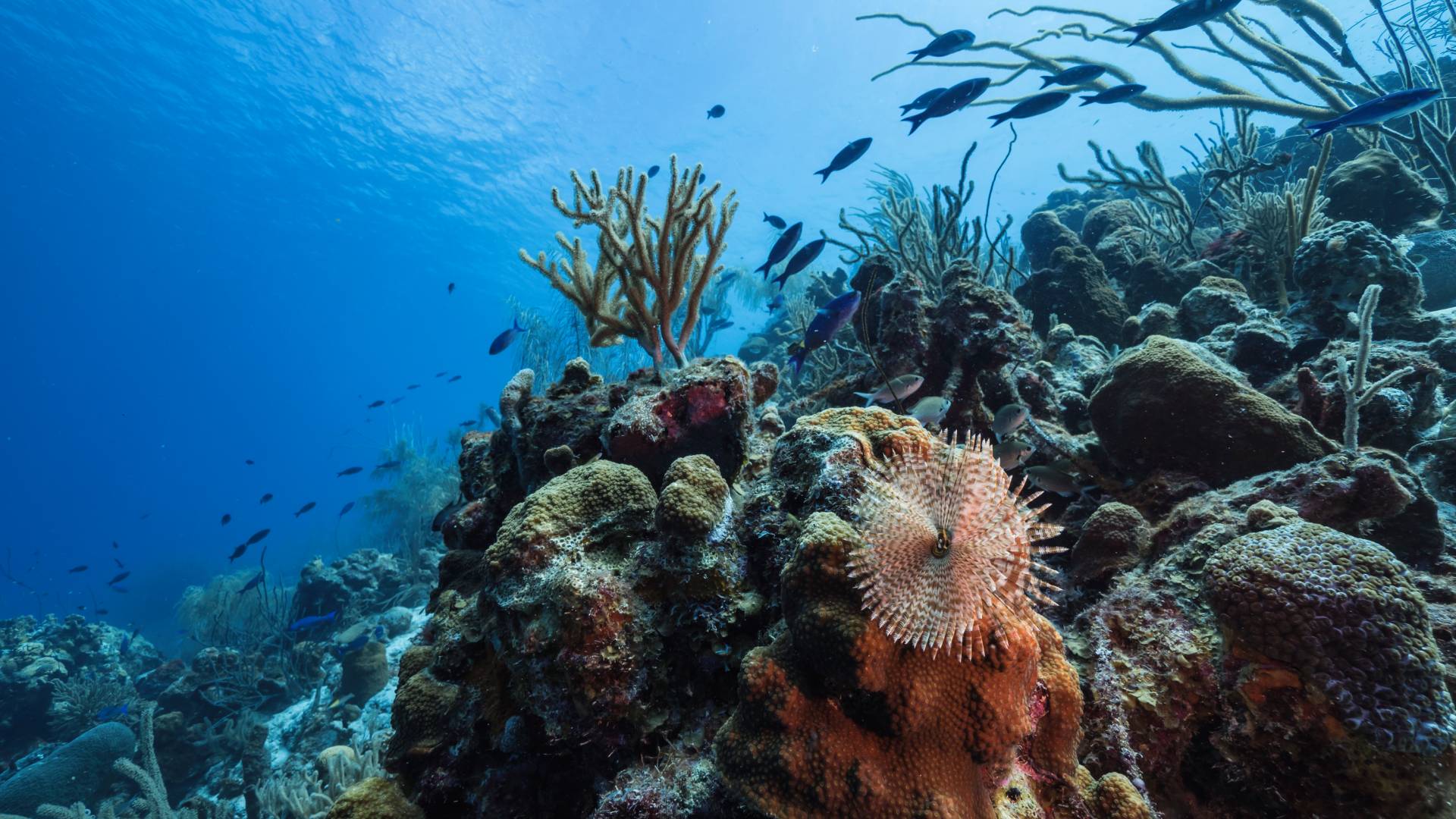

The ocean covers over 70% of the planet. It produces oxygen, stores carbon and feeds millions. It is home to vast biodiversity, with an estimated 500,000 to 10 million species, many of which are still undiscovered.

Yet the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, adopted by 192 countries in December 2022, like many international agreements before it, has failed to proportionally prioritise the ocean. Despite threats to marine ecosystems from overfishing, pollution, and habitat destruction, global conservation efforts remain overwhelmingly focused on terrestrial environments.

The ocean, carbon storage and climate

Consider carbon storage. Mangroves, seagrasses, and coastal ecosystems play a crucial role in sequestering carbon, and the ocean absorbs around a quarter of global CO2 emissions annually. Damage to these environments threatens our planet’s capacity to combat climate change. This in turn exacerbates increasingly severe weather events and other threats to forests, wetlands, and biodiversity on land. Inattention to marine ecosystems in biodiversity planning undermines efforts to protect coastal livelihoods, food security and critical ecosystem services such as shoreline protection, climate regulation, carbon storage and nutrient cycling.

Underfunding of marine biodiversity work deepens this crisis. SDG 14, dedicated to life below water, is one of the most underfunded of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Most international public biodiversity finance focuses on terrestrial and freshwater biodiversity, with only about 4% of bilateral biodiversity-related Official Development Assistance (ODA) addressing marine biodiversity. The lack of investment is alarming considering the economic security and essential services the ocean provides for millions across the globe.

The effects of biodiversity loss

The consequences of ignoring marine biodiversity are stark. Over 25% of marine mammals are now at elevated risk of extinction, and nearly 38% of fish stocks are considered overexploited, threatening global food security. In my career as a marine scientist, the global population has just about doubled, putting significant pressure on ocean resources for food and livelihoods, along with major increases in marine pollution and biodiversity loss. We cannot afford to delay action. The ocean is the foundation of our planet’s environmental and economic health, and its neglect has long-term repercussions for life on land.

Fortunately, public awareness of the marine biodiversity crisis has risen rapidly. Twenty years ago, when I began my marine conservation career with the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, we only had detailed knowledge of the conservation status of about 1500 marine species, comprising mostly of marine mammals, sea turtles and seabirds. Since then, the IUCN has systematically worked to assess the conservation status of almost 20,000 marine species, comprising major habitat-forming species, such as corals, mangroves and seagrasses, and most of the world’s marine fishes. But we are still far from understanding the distribution, population and conservation status of the hundreds of thousands of marine species, including deep sea fishes, marine invertebrates and seaweeds.

Positive progress

While the overwhelming scale and speed of global biodiversity loss can feel disheartening, progress is being made. Both the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and the MSC’s science-based standards have been recognised in the Kunming Biodiversity Framework as robust tools to measure efforts to reverse marine biodiversity declines. For example, MSC certified fisheries maintain healthy fish populations and minimise bycatch, benefiting the broader marine ecosystem, and with evidence that the fish stocks they target are more abundant. For instance, fishers in Northern Australia using Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) have achieved a 99% reduction in turtle bycatch. Similarly, the Namibian hake fishery has reduced seabird deaths by 98% with bird-scaring lines.

As government delegations gather at COP 16, they must ensure that marine biodiversity is an integral part of the conversation. The ocean must be fully represented in NBSAPs and backed by appropriate political and financial commitments. NGOs, campaigners, funders, and journalists must hold governments accountable and push for comprehensive, interconnected conservation strategies.

The decisions made at COP 16 will shape the future of biodiversity on this planet. We must act now to ensure that marine ecosystems are protected and sustainably managed alongside terrestrial environments. Preserving the ocean is critical for planetary and human health and is our greatest ally in combating biodiversity loss and climate change. We must create and act on marine conservation policies now before it is too late.