Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic, with just 245 inhabitants and an MSC certified lobster fishery, has a new Marine Protected Area to keep its waters sustainable.

Tristan da Cunha, the world’s most remote inhabited archipelago © istock.com/Grant Thomas

Tristan da Cunha, the world’s most remote inhabited archipelago © istock.com/Grant Thomas

Before dawn two experienced fishermen on the island of Tristan da Cunha will observe the weather. If it is deemed fair, they will sound a “dong” to announce a fishing day.

On hearing the call, plumbers, electricians, mechanics and other members of the government will go to the MSC certified fish factory. Post office workers, supermarket staff, clerks and retirees then follow in the evening to help pack the prized lobster catch.

Life on the world’s most remote inhabited archipelago is dominated by the weather. Buffeted by storms from the Southern Atlantic, Tristan’s four volcanic islands sit some 1,510 miles west of Cape Town. Fishing in small, seven-metre island boats can only take place when the weather is fine, which is limited to 30 to 40 days a year.

Without a landing strip, the British Overseas Territory can only be accessed by a week-long boat journey. The island harbour is only accessible for around 90 days of the year and, under Covid-19 restrictions, visiting crew and passengers from all vessels must be tested and wait 14 days before disembarkation.

With a current population of just 245 people, only the main island is permanently occupied. In 1961, a lava flow threatened its main settlement, Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, forcing the islanders to evacuate and reside in the UK for two years.

Adorning the island’s flag are two rock lobsters, illustrating the pivotal role crustaceans play in the life of Tristanians. The fishery, which processes the temperate rock lobster species, is a mainstay of the island economy contributing 80 per cent of the territory’s revenue.

“Looked after, the island will always have a future,” declares Chief Islander James Glass. “This is why we look after the fishery so well.

“Over the years I have seen fishermen do harmful practices that have made me want to work towards a sustainable fishery. I and the islanders believe that you should only kill what you need and can use.”

The Tristan da Cunha flag adorned with two rock lobsters. © istock.com/sansak

The Tristan da Cunha flag adorned with two rock lobsters. © istock.com/sansak

Marine Protected Area

Four years ago, Tristan made a commitment to the UK government to help implement its target to protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030.

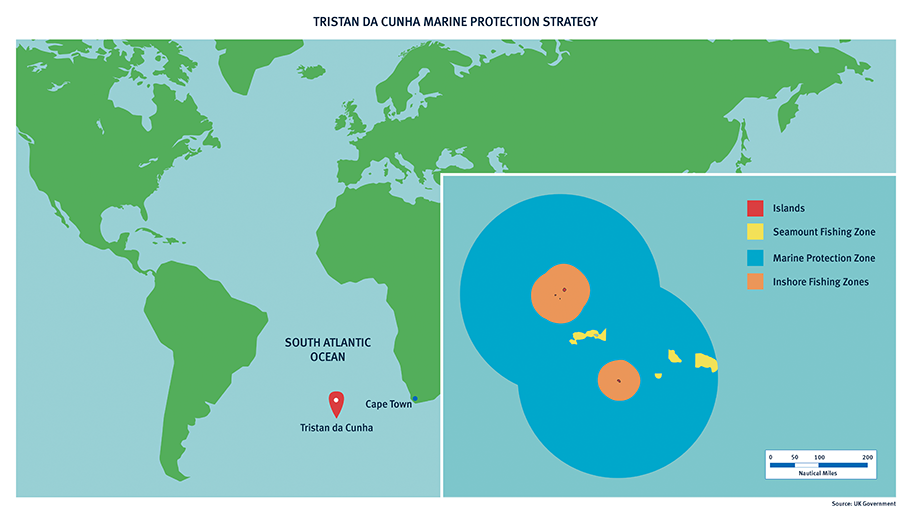

This November the island announced that almost 700,000 sq km of its waters would become a Marine Protected Area (MPA), the fourth largest such sanctuary of its kind in the world and the biggest in the South Atlantic.

The UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson released a video praising Tristan for doing its part to “close more than 90% of its waters to harmful human activity”.

“We're glad that we could help the UK in some way,” says Glass with understatement. “We are a small community and I think we've been quite lucky that the British government has looked after us so well, so if we can help them beat that target that is all well and good.”

A Marine Protected Area or zone offers varying levels of protection by regulating fishing, diving and boating, particularly those who carry out illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) activities. To tackle the underlying problem of overfishing, MPAs should be combined with sustainable fishing practices so the problem is not simply moved from one place to another.

Tristan does this and more. According to Hugh Jones, principal fisheries manager of Control Union, the assessment body which confirms whether the Tristan fishery meets the MSC Fisheries Standard, the “independent research has shown that the marine environment in the fished area of Tristan had biomass comparable to or greater than many of the MPAs around the rest of the world”.

Tristan da Cunha archipelago with MPA and fishing zones © Becky Moriarty for MSC

Tristan da Cunha archipelago with MPA and fishing zones © Becky Moriarty for MSC

MSC certification opens up new markets

Tristan began exploring MSC certification in 2008, with independent assessors confirming its status in 2011. “It added value to the product and many markets only want products with the MSC label on,” opines Glass.

The archipelago is used to dealing with adversity. In 2001 a hurricane wrought devastation, leaving the island without electricity for six days. Seven years later, the fish factory burned down before being rebuilt to EU standards. Last year, a storm severely damaged Tristan’s main administration building, police station, post office and school.

“We’ve had quite a few disasters,” says James matter-of-factly, “but the Tristanians are a resilient people. We come together as a community and we make it work.”

Endemic to the Tristan da Cunha island group, the rock lobster is “sold as a sashimi-grade product,” says Michael Marriott, the MSC’s senior program manager for Africa, the Middle East and South Asia (AMESA). Popular in the US, Japan and Australia, markets have opened up in the European Union as well following MSC certification.

Marriott says there are “sporadic wildlife interactions” with seabirds from the main vessel. The most recent assessment report found there was zero bycatch because the small amount of other fish – such as octopus – can also be kept and used as food in a sustainable way.

“Tristan is one of the few MSC certified fisheries that currently has no conditions on its certification,” says Marriott. “All certified fisheries are deemed sustainable, but the Tristan fishery is amongst a handful that is achieving best practice across all performance indicators.”

Around 400 tonnes of lobster are landed each season which runs between the 25 August and the 30 April. The Tristan small local boats are allowed out from the 1 July. This is because they only work during daylight hours with no gear allowed to be left overnight, to avoid catching egg-carrying lobsters.

Since entering into commercial fishing in 1949 the archipelago has controlled a 50-mile zone around the four islands that is closed to other fishing methods. This area acts as a buffer between the lobster fishery – which only goes out to a maximum of around six miles – and other commercial fishing in the wider ocean. (At the southern Gough Island the zone was reduced to 40 miles in November 2020).

Three types of gear are used in the fishery: powerboat traps, hoop nets and monster traps. Box traps are deployed from small boats around all four islands, hoop nets are deployed from powerboats at Tristan only, and monster traps are deployed from the main boat at the three outer islands.

A standard mesh size of 70mm is used on all the traps. All three gear types are open – so lobster entering the traps can also exit at will by the same opening. There is therefore no risk of ghost fishing by lost traps, and no need for escape gaps to release undersized lobster.

The fishery has also successfully addressed how it operates to reduce the risk of seabirds accidentally being harmed when they encounter the fleet.

Tristan has a royalty agreement with South African-based company Ovenstone Agencies (PTY) Ltd which, since 1999, has operated the lobster fishery under a sole concession granted by the government.

Ovenstone operates a vessel from Cape Town to fish around the three outer islands which include Gough Island, Inaccessible Island and Nightingale Island. Lobster caught by this vessel is processed on board to EU standard.

A fleet of small boats, operated by Tristan fishermen, is used to catch the quota allocated to Tristan, the only inhabited island in the archipelago. The catch from these small vessels is processed at the factory situated on the main island.

Ovenstone provides eight voyages a year from Cape Town carrying lobster, cargo, medical supplies and passengers to and from Tristan. “From our perspective, it feels like we are in partnership with the islanders,” says Dorrien Venn, a director of Ovenstone Agencies.

James Glass pictured with two temperate rock lobsters. © James Glass

James Glass pictured with two temperate rock lobsters. © James Glass

'You could call it Utopia'

“The first time I went there in 1998 I witnessed how people had made a life for themselves. Most Tristan residents were self-sufficient and getting on fine without that direct connection to the outside world.

“Back then there was one radio and one telephone. While there is WiFi, British Forces TV and WhatsApp now, there is still a big sense of community where everyone looks after each other. A lot of people don’t want to leave the island because of that. You could call it Utopia for some.”

Until October of this year, Ovenstone’s main fishing vessel was the MFV Geo Searcher. That month the 70-metre vessel sank off Gough Island. A second support vessel, the MFV Edinburgh, has been reconfigured to catch the remaining quota for the 2020-21 season.

“It is a setback,” says Venn, “but we will get through it. The main thing before anything else is that there were no human casualties. We will get through the season and make sure we land the full quota. We are going flat out to find a replacement fishing vessel.”

The pandemic has hit sales of lobster into restaurants. “Obviously our revenue will be down this year,” says Glass.

“Tristan is not a prosperous island and it will have an economic impact but we don't have any debt. We don't have a lot of money to spend either, but we will get through this.”

MSC labelled products from Tristan da Cunha

- Woolworths Food Cooked Tristan Crayfish 250g, Greys Marine CC (South Africa)

- Carrefour Selection Langouste rouge 340g, Semegel International (France)