A symbol of reconstruction, a game-changer for young fishers and a pioneer within the sashimi market, the newly MSC certified, family-run Usufuku Honten tuna fishery has been providing seafood to Japanese consumers for more than five generations.

"The ship swept away, overturned, burned in flames, pierced a building and rolled into a rice field. The black muddy stream of the tsunami hit an oil storage tank, and at night, the oil ignited and a red flame covered the sea. It even hit the town.” This is an eyewitness account from Usufuku Honten employee, Nobuhiro Owada, given to Forbes about the devastation caused by an earthquake and subsequent tsunami, which destroyed most of the Japanese coastal town of Kesennuma in 2011.

Along with the town’s entire fishing port, which had long been on the map as one of the most productive in Japan, Usufuku Honten’s office, vehicles and warehouse were also destroyed. The earthquake and tsunami resulted in the death of 1,357 people, 15,815 devastated houses and 9,500 affected households in Kesennuma city.

Along with the town’s entire fishing port, which had long been on the map as one of the most productive in Japan, Usufuku Honten’s office, vehicles and warehouse were also destroyed. The earthquake and tsunami resulted in the death of 1,357 people, 15,815 devastated houses and 9,500 affected households in Kesennuma city.

The tragic events marked the start of a new era for the fishery, which had been operating for more than 100 years. Established in 1882, Usufuku Honten was originally a seafood wholesaler and later began fishing in the 1930s. Since the 1980s, the fishery focused on tuna fishing in the Atlantic Ocean. Today, the fishery employs 207 staff and owns seven distant-water longline fishing vessels.

Rebuilding after the earthquake

"Among the remains of the Usufuku Honten office, I looked for our list of phone numbers so I could contact and check all our employees were safe,” says Sotaro Usui, president of Usufuku Honten.

Usui saw multiple vessels wash ashore the day after the tsunami: “None of them belonged to us as our vessels had been operating offshore. But some of our fishers’ family members had died.”

In the days ahead, Usui came to a realisation that would change the course of the Usufuku Honten fishery for years to come: “I lived like a refugee, surviving on one onigiri (a Japanese rice ball), per day. I quickly learned that I could live without clothes or shelter. But I couldn’t survive without food.”

Tsunami destruction in Kesennuma © Horizon Images/Motion Alamy Stock photo

Tsunami destruction in Kesennuma © Horizon Images/Motion Alamy Stock photo

After the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, the word Kizuna (絆), which in Japanese means to bond together or connect people, became extremely popular in Japan. Usui adds, “I then understood that it was my responsibility to provide food to current and future generations.”

Usui was also concerned by the high levels of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing within the bluefin industry. Between 1998 and 2007, the black market included more than one out of every three bluefin tuna caught. “I endeavoured to differentiate ourselves from these fisheries with unsustainable management”, said Usui.

Fast forward nine years and on 12 August 2020, Usufuku Honten became the first bluefin tuna fishery in the world to gain MSC certification for sustainability.

A world first

“We observe the world’s strictest catch management. We will change the industry – I don’t think we have the option not to. If bluefin tuna is to have a secure future then Japan must find more sustainable ways to catch the fish,” declares Usui.

Usufuku Honten target (Eastern) Atlantic bluefin tuna: one of three bluefin species found around the world. Eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna’s path to certification is all the more extraordinary, as its future was in doubt just 15 years ago.

Bluefin tuna underwatwer © Paulo Oliveira/Alamy Stock photo

Bluefin tuna underwatwer © Paulo Oliveira/Alamy Stock photo

Years of environmental activism, dramatic quota reductions and management measures which included increased scrutiny and reporting, put the Eastern Atlantic bluefin population on a path for recovery.

Usufuku Honten fishes for its allocated quota of Eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna during October, catching an average of 292 bluefin tuna annually, weighing around 150kgs each. This equates to less than 0.2% of the total allowable catch for 2020 set by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).

Every bluefin tuna caught by the fishery is then electronically tagged with a tamperproof serial number, which indicates the date, time and location where the fish was caught. The tagging is part of a Japanese government-led trial which tackled seafood fraud: the selling of food products with a misleading label, description or promise. “I wanted to differentiate the seafood caught by Usufuku Honten from others, including imported and farmed fish, so we voluntarily joined this trial. The trial ended last year but we have chosen to continue tagging ourselves,” Usui explains.

After being tagged, the fish are quickly frozen onboard and securely shipped to Japan, destined to be eaten as top-quality sashimi. If the weight recorded at catch exceeds the allocated quota, the Japan Fisheries Agency can fine the fishery as part of its efforts to tackle seafood fraud; a global problem which has significant impacts on both the marine environment and seafood industry.

The vessel being used to catch bluefin tuna, the Shofuku Maru No. 1, is based in the Canary Islands, Spain. The vessel is quite unlike any other fishing ship you’re likely to see.

Attracting the next generation of fishers

Usui is part of a programme that promotes the fish caught in Kesennuma within the catering departments of local schools. From visits to the Usufuku Honten fishing vessels, to parent and child cooking classes, it provides school children with an opportunity to learn about the fishing industry from a young age.

To attract the next generation of fishers, Usui went one step further and reached out to a world-class designer, Oki Sato of the Japanese design firm Nendo, with the aim of creating ”a ship that crews wanted to ride”.

“The first draft was extraordinary. The proposal was a black ship covered with a traditional Japanese pattern!” laughs Usui. Interiors of the Shofuku Maru No.1 © Usufuku Honten

Interiors of the Shofuku Maru No.1 © Usufuku Honten

Facilities onboard the Shofuku Maru No.1 look more akin to those found on a luxury yacht than a fishing vessel - which include superfast Wifi and a relaxation area. “The aim was to alleviate the stress of being at sea for long periods of time,” explains Usui. Being out at sea can be strenuous on the mental and physical wellbeing of fishing crews. According to Usufuku Honten, this stress results in a turnover rate of more than 50% among younger crew who work on longline vessels.

“There is no point in building a ship if there are no sailors to pick up the fish,” states Usui, who is concerned about the increasing numbers of Japanese people migrating from the coast to cities. Indeed, the number of workers engaged in marine fisheries and the aquaculture industry in Japan is declining. In 2017, Japanese fisheries employed approximately 153,000 workers, down from almost 203,000 thousand workers in 2010, according to business data platform Statista.

A pioneer within the sashimi industry

The certification of Usufuku Honten to the MSC Fisheries Standard means that Japanese consumers will now have the option to choose sustainable bluefin sashimi in high-end restaurants. Sashimi, a Japanese delicacy, refers to raw meat or seafood that is thinly sliced. It is often confused with sushi which contains vinegared rice.

Approximately 80% of the global bluefin catch from the Atlantic and Pacific is consumed in Japan, where it is commonly served raw as sashimi and high-grade sushi.

Bluefin tuna sashimi © akai27

Bluefin tuna sashimi © akai27

According to Usui -- who chairs a national tuna fisheries council tackling illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing - if bluefin is to have a secure future then Japan needs to find more sustainable ways to catch the fish: "Fisheries can’t solve overfishing and IUU by themselves, the whole market needs to tackle it."

Overfishing of Atlantic bluefin tuna in the 1990-2000s was largely a result of the demand for bluefin in upmarket sushi markets around the world. According to a United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation 2017 report, while consumption of sushi and sashimi is declining in Japan - due to consumer preference changes and demand for lower-cost foods - it continues to grow in other countries.

Usui is conscious of people who say it is too soon to certify any bluefin tuna, when other stocks around the world are still unsustainable. He believes the best way to achieve this is to lead by example. “This certification is just a start,” says Usui. “Fisheries and conservationists share the same goal: working together for sustainability.

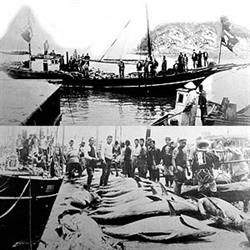

Black and white photo of tuna landings in 1952 courtesy of Usufuku Honten Co Ltd.